Life Sciences

Helping People to Lead Better Lives

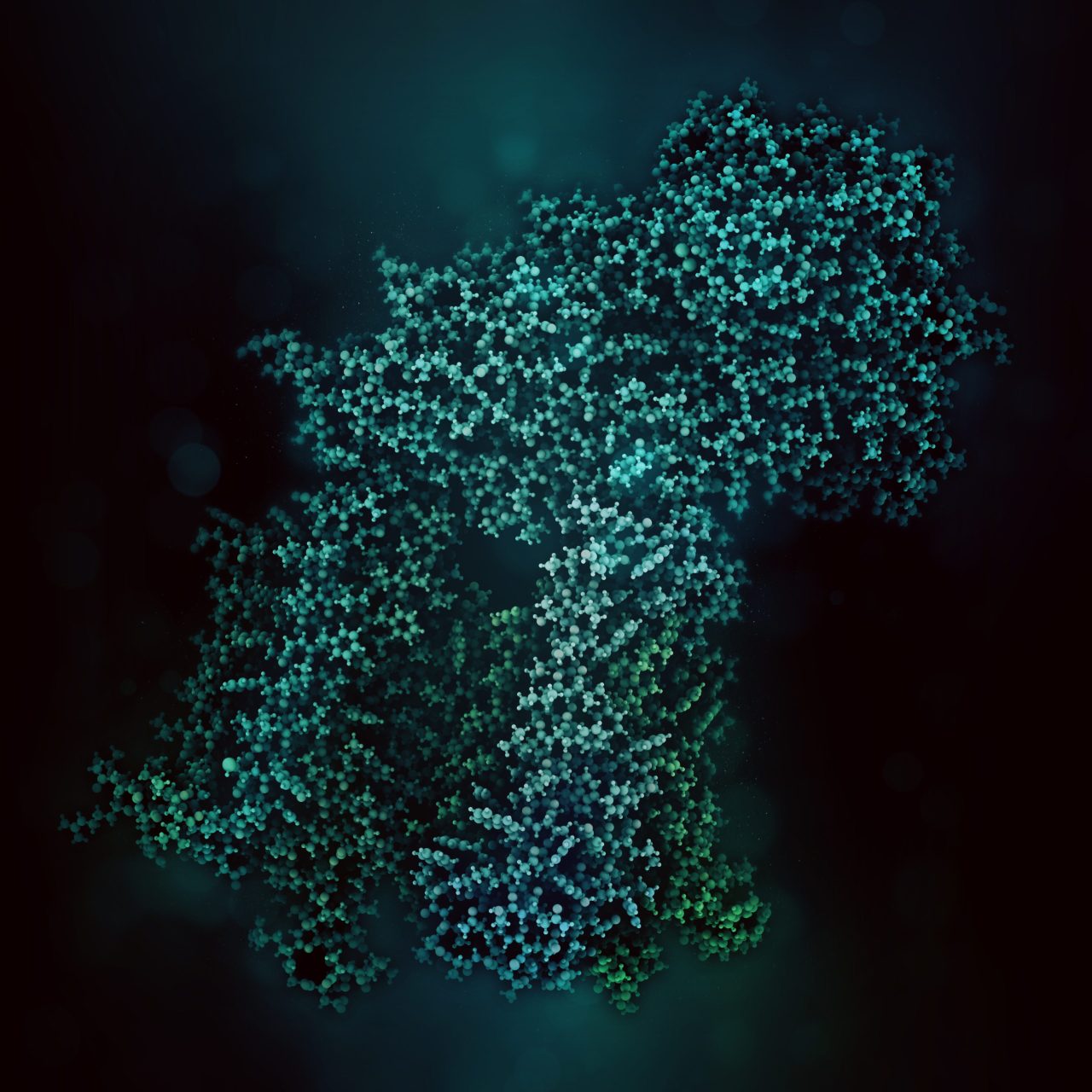

Life science is changing rapidly and constantly. New discoveries lead to more efficient and faster development of innovative molecular research methods as well as small and large molecular therapeutics – thus creating a basis for sustainable growth in these markets. With innovative solutions Bruker supports pharmaceutical companies, research institutes and development organizations in driving therapeutical advancements, managing costs, expanding analytical capabilities and significantly increasing productivity.

Add Automation to your instrument

Automation is revolutionizing the way laboratories operate, and Bruker is at the forefront of this transformation. By integrating advanced automation solutions, we empower researchers and scientists to achieve unprecedented levels of efficiency, accuracy, and productivity.

Our automation technologies streamline complex workflows, reduce manual errors, and ensure consistent, high-quality results. With Bruker's automation solutions, you can focus on innovation and discovery, while we take care of the rest.

Learn more about the Flex EP for fully automated eluent preparation.

For Research Use Only. Not for use in clinical diagnostic procedures.