Hardness Testing of Metals: Micro vs. Nano

Hardness testing is a widely utilized methodology in materials science for localized determination of the resistance to plasticity in metals. Two of the most common techniques are microindentation and nanoindentation, each with its own advantages and applications.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Microindentation

Microindentation, also known as microhardness testing, uses a prescribed force to press a diamond tip into the metal's surface. This method is suitable for testing larger volumes of material compared to nanoindentation. However, the operating principle of microhardness testers limit the scale of testing and speed which results can be obtained.

Measuring Residual Indent Impression

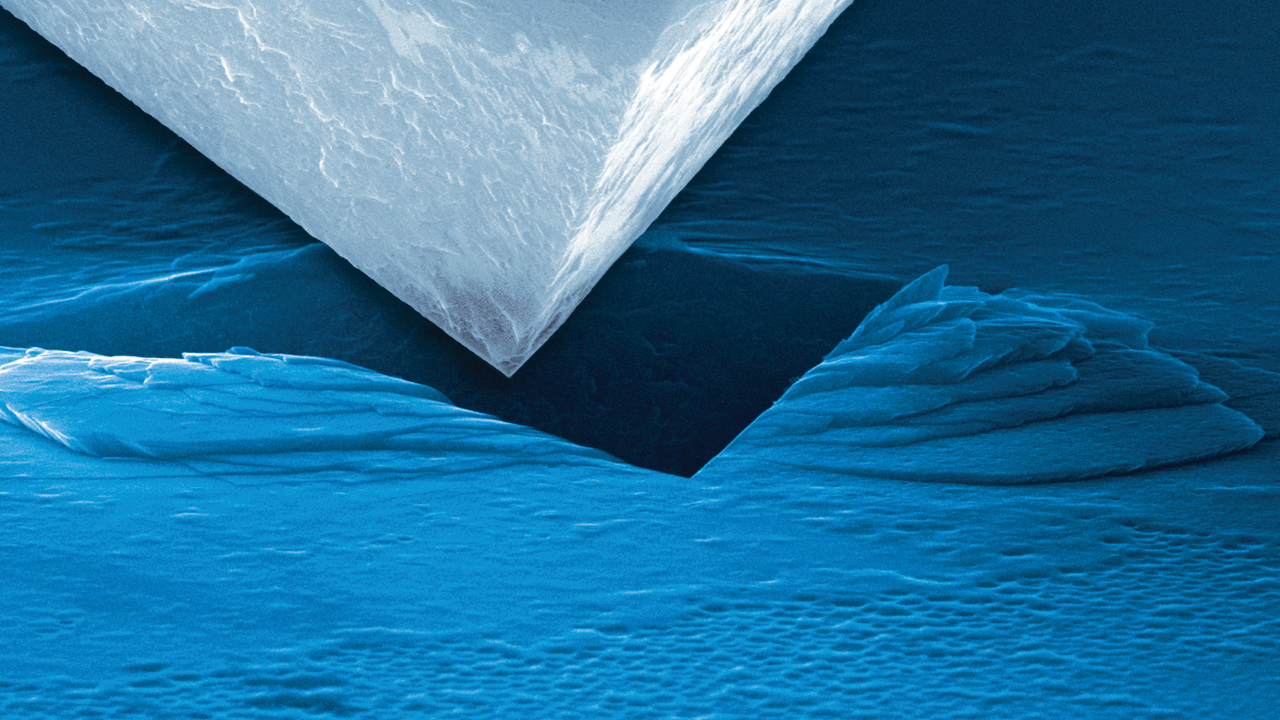

In microhardness testing, the size of the residual indent impression needs to be measured optically after the load is removed. The Vickers hardness value (HV) is calculated from the average length of the two diagonals of the indent and the applied force. This optical measurement requires high accuracy and significantly limits the length scales at which it can be used.

Average Result Within Sampling Volume

Indentation provides an averaged hardness value over the sampling volume, which, in the case of microindentation, is typically much larger than an individual microstructure component and thus gives a composite response of many components. This can be useful data, but this makes it difficult to measure differences between individual grains or phases within the metal. Additionally, metallic films and coatings may be too thin to reliably use microhardness testing.

Nanoindentation

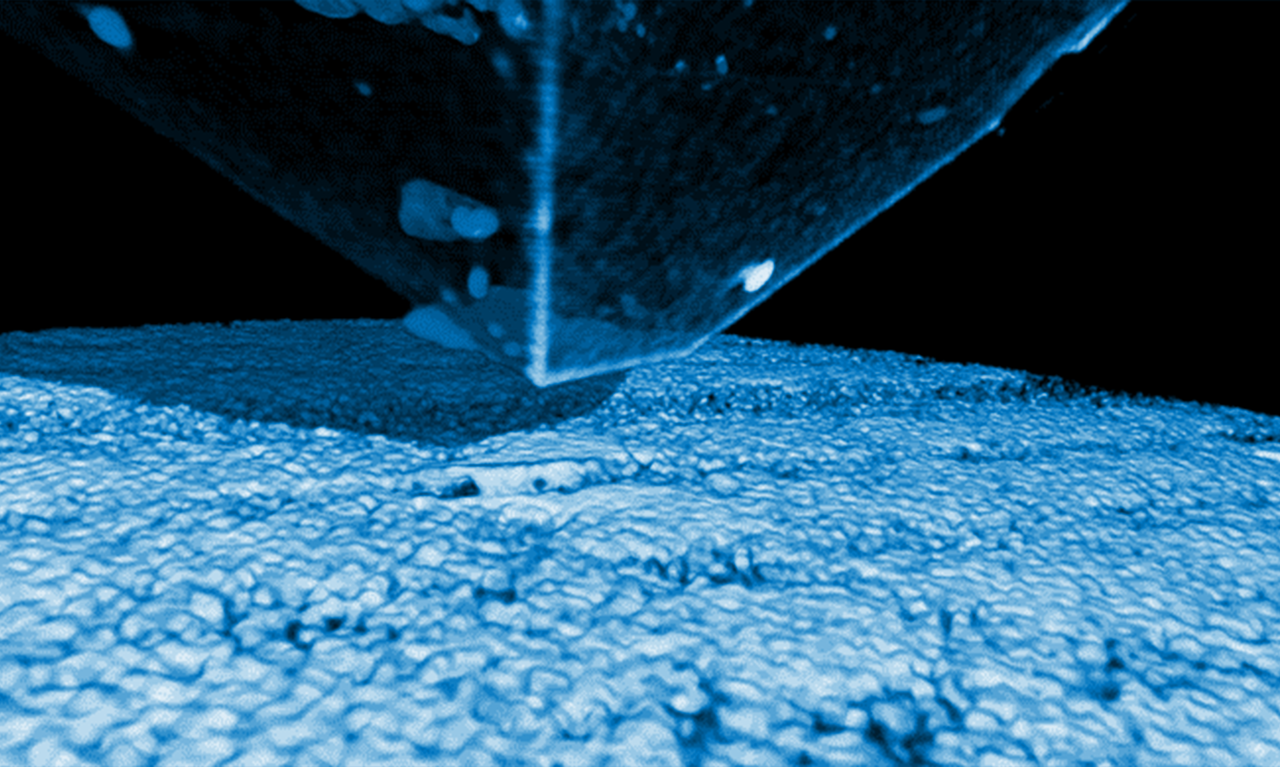

Nanoindentation is a more advanced technique that allows for the measurement of mechanical properties at the nanoscale beyond just hardness. This method uses a sharper indenter probe and high-sensitivity transducer to test at smaller scales than microindentation. Nanoindentation, also known as depth-sensing instrumented indentation, gathers detailed information about the metal's properties through acquisition of a continuous load-displacement curve. By utilizing contact mechanics to determine contact area from the load-displacement data, an optical measurement of the residual indent impression is not required. Depending on the length scale that need to be characterized, nanoindentation can have several advantages over microindentation:

Measurement of Elastic-Plastic Properties

Nanoindentation not only measures the plastic properties (i.e., hardness) but the elastic-plastic properties of metals. By analyzing the load-displacement curves, nanoindentation provides data on both hardness and elastic modulus simultaneously, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the material's mechanical behavior. Furthermore, excursions in the load-displacement curve can be used to identify critical loads for fracture and delamination, and creep and stress relaxation behavior can be quantified through modification of the load function to incorporate holding segments.

Higher Resolution and Sensitivity

Nanoindentation can measure extremely small volumes of metal, providing high-resolution data on mechanical properties such as hardness, elastic modulus, and creep behavior.

It is particularly useful for studying thin films, coatings, and small individual phases within metals that are not accessible with microindentation. Furthermore, as will be demonstrated further down, high throughput nanoindentation can also use many measurements in a similar amount of time to give a comparable averaged response to microindentation

Enhanced Data Accuracy

The precision of nanoindentation ensures more accurate measurements of mechanical properties, eliminating the measurement errors associated with determining the size of the residual indent impression.

Detailed Mechanical Property Mapping

This technique allows for the creation of high-resolution maps of mechanical properties across a metal surface, which is beneficial for studying heterogeneous materials and understanding local variations in properties. The increased spatial resolution of nanoindentation can also reveal property gradients due to heat affected zones, local chemistry changes or damage zones in much greater detail.

Reduced Sample Size Requirements

Nanoindentation requires significantly smaller sample volumes compared to microindentation, making it ideal for testing metals that are available only in limited quantities.

Versatility in Testing Conditions

The smaller sample size for nanoindentation makes it comparatively easier to control the environmental conditions while testing, such as high temperature, cryogenic temperature, humidity and in fluid. When combined with precise control over strain rates, metals can be studied under specific operating conditions.

Comparing Nanoindentation to Micro Vickers Hardness Testing

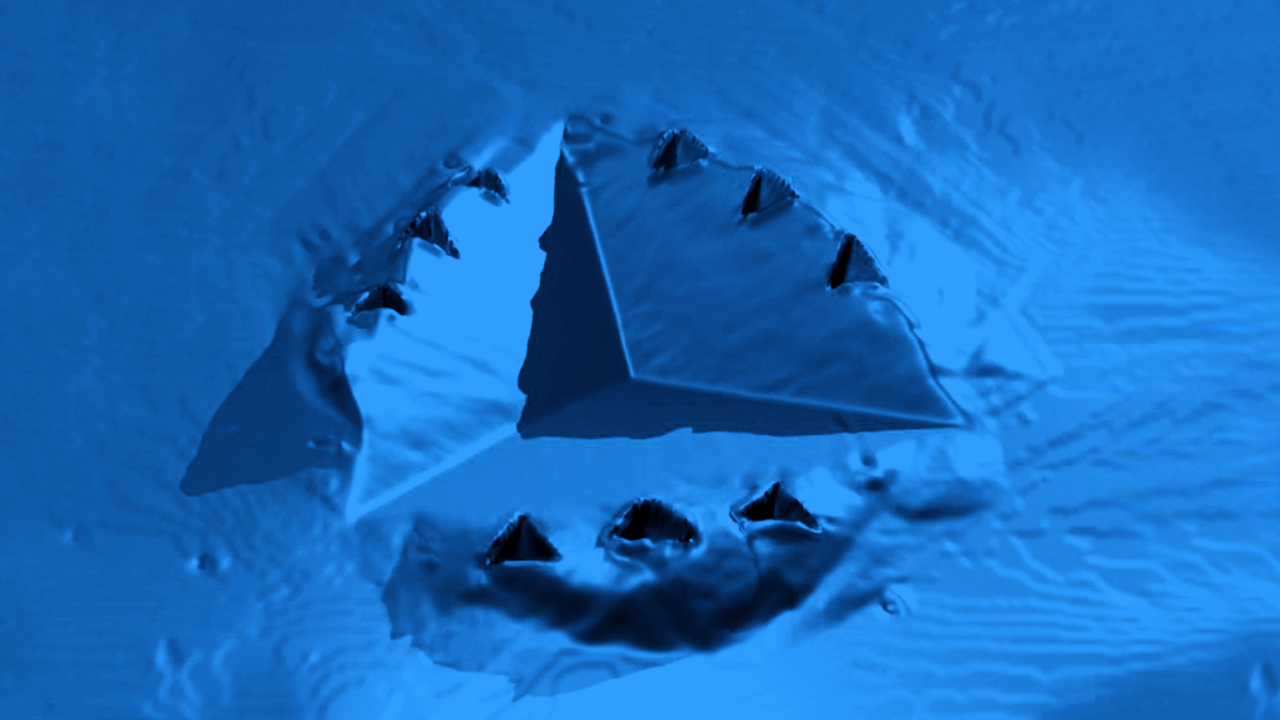

Different probe geometries are available for both nanoindentation and microhardness testing, with Berkovich and Vickers geometries being the most popular. Both probes are pyramidal in shape with the same aspect ratio, making them analogues of each other. However, the Berkovich geometry used for nanoindentation has three sides compared to the four sides on the Vickers geometry. Three intersecting planes will always meet in a point, allowing Berkovich probes to be sharper than their microhardness counterparts.

ISO 14577 provides a standardized formula for converting nanoindentation hardness (HIT) values to Vickers hardness (HV) values and takes the form HV = 0.0945HIT for a Berkovich probe. This conversion is essential for comparing results obtained from different hardness testing methods.

Nanoindentation vs. Microhardness, a Direct Comparison

The average hardness value obtained using nanoindentation mapping (on the surface right next to a micro-Vickers measurement), with the ISO 14577 conversion, produces nearly identical values as the Vickers hardness value.

Hardness Distribution Statistics:

Nanoindentation provides detailed hardness distribution statistics within the same surface area. This means that while micro-Vickers gives an average hardness value over a larger area, nanoindentation can reveal variations in hardness at a much finer scale, providing insights into the local mechanical properties and heterogeneity of the metal.